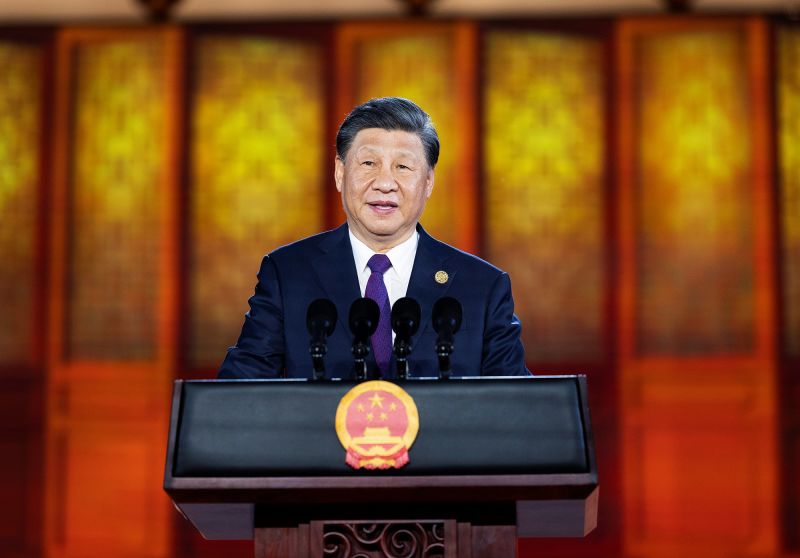

Chinese leader Xi Jinping is gathering world leaders in Beijing this week for a high profile forum with a clear set of goals: laud China’s role backing economic development over the past decade and project its expanding ambitions as an alternative global leader to the United States.

That bid takes on heightened significance as renewed conflict in Israel and Gaza threatens to trigger broader instability in the Middle East, a region where the US is the traditional power broker, but China has been growing its influence and efforts to play a role in peace.

Leaders, representatives and delegations from more than 140 countries, including in the Middle East and many Global South nations, are expected to meet in the Chinese capital for the carefully choreographed two-day gathering – China’s first time hosting an international event at this level since emerging this past January from nearly three years of pandemic isolation.

Beijing has been remarkably close-lipped in the lead-up to the event, an important milestone for Xi marking a decade since the launch of his signature foreign policy, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), hailed by officials as China’s “most important diplomatic event” of the year.

Officials only announced the dates six days before the forum’s start, and did not release a list of attendees in advance as of Monday morning, a day before the event.

Likely missing from that guest list are top leaders from major Western powers, at least some of whom, a Chinese state-run media outlet earlier this year implied, weren’t invited.

Russia’s Vladimir Putin, whose on-going assault on Ukraine is another major point of global instability and division, is expected to attend. The last time he was in Beijing was for the Winter Olympics opening ceremony in early 2022. Three weeks later, Russian tanks and troops poured over Ukraine’s border.

The forum will signal the future path for Xi’s Belt and Road, which for the past 10 years funneled hundreds of billions in Chinese financing toward building ports, bridges, highways and power plants largely in poorer countries across the world, expanding China’s global influence along the way.

But Chinese officials, experts say, will also use the gathering of friendly countries to pitch a much broader vision for how China wants to impact the world, as it promotes an alternative to the liberal world order championed by democratic countries.

“Xi’s message is clear – the current, US-led order has failed to bring either peace or prosperity to many developing nations, and a new order is necessary to tackle today’s issues and anticipate tomorrow’s challenges,” said Craig Singleton, a senior fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies think tank in Washington.

“He wants to be seen as being capable of convening world powers in Beijing and (of demonstrating that) when he hosts a summit there is a deliverable outcome … (including a) very clear path forward to discuss reforming global governance,” he added.

China’s way

Xi’s bid comes at a critical time for Beijing.

It faces stark economic challenges at home with a spiraling property crisis, high unemployment and slowing growth – and sees its rise increasingly threatened by what it believes are American efforts to contain and stifle its development.

The Chinese leader is also grappling with apparent turmoil in the top echelons of the ruling Communist Party. Beijing abruptly replaced several senior officials including its foreign minister without explanation this summer. Its defense minister has not been seen in public since August amid reports suggesting he is under investigation.

Winning backing for China’s global leadership from a broad swath of developing and emerging economies is key to Xi’s strategy to push back against perceived international threats, analysts say.

This week in Beijing Xi will be surrounded by nations like Russia, who have grown increasingly aligned with China – especially as Putin’s brutal invasion of Ukraine has drawn the US and its allies closer together, while Moscow and Beijing have looked to strengthen alternative groups like BRICS and make them more explicitly anti-West.

In an interview with Chinese state broadcaster CCTV broadcast Sunday ahead of the event, Putin lavished praise on Xi, hailing his “unique approach of dealing with other countries” that has shown no imposition or coercion, but rather providing others with opportunities.

In a sweeping more than 13,000-word policy document released last month ahead of the forum, Beijing laid out the broad strokes of its international vision, warning the world “is at risk of plunging into confrontation and even war.” China “lights the path forward” with a plan to “promote solidarity and cooperation among all countries,” it said, while providing limited specifics.

The pitch appears at odds with accusations from countries in China’s region that it is itself threatening regional stability with its aggression, including in the disputed South China Sea – claims Beijing rejects.

During the forum, Chinese leaders will likely cite the latest outbreak of conflict between Israel and militant Islamist group Hamas as another example of “how the various Chinese ideas and proposed principles may help better address regional security challenges,” according to Li Mingjiang, an associate professor of international relations at Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University. Officials have made similar suggestions throughout the conflict in Ukraine.

But the latest conflict may also spotlight limits to China’s ability to play a role in its resolution.

Israel last week expressed “deep disappointment” with Beijing’s response to the conflict, which follows a terror attack on Israeli territory by Hamas, in particular its failure to explicitly condemn Hamas terrorism in its statements.

Most actors in the region may not see China as a player that can fundamentally address these issues, as this remains “an early moment in China’s Middle East presence,” Jonathan Fulton, an Abu Dhabi-based senior fellow at the Atlantic Council think tank, said.

Even as Beijing may look to pitch its larger ambitions on the world stage this week, many delegations attending this week’s event will be more interested in enhancing their economic partnerships with the world’s second largest economy and getting a sense for how China will direct funding into the Belt and Road Initiative in the years to come.

Some governments in the Middle East are “laser focused” on how cooperation with China and the BRI can facilitate development, according to Fulton. “There’s a massive appetite for that in the Middle East.”

Belt and Road ahead

Ten years on, the initiative itself has a mixed legacy.

It has propelled construction of much-needed infrastructure and development projects in poorer countries across the world to the tune of what Beijing has said is “up to one trillion dollars of investment.”

It’s also pushed other powers to beef up their own efforts. Last month, the US and its partners pitched the latest of those rival programs on the sidelines of the G20 summit in New Delhi.

But Belt and Road projects have also sparked backlash over accusations of lax environmental and labor standards – and of saddling some countries with unmanageable levels of debt, an issue now compounded by a shifting financial environment in the wake of the pandemic and war in Ukraine.

A report from the Boston University Global Development Policy Center released earlier this month found that Chinese development finance projects carry significantly higher risks to biodiversity and to Indigenous lands than projects financed by the World Bank.

Overseas development finance from China’s two major development banks has also decreased significantly since a peak in 2016, the report’s data show.

China has pushed back on criticisms of the initiative, but also signaled ahead of the forum that there will be a shift to environmentally friendly, better-vetted projects in the years ahead.

The next stage of BRI will continue to create “high-quality” projects that can “better benefit people in partner counties,” Cong Liang, a top official with China’s National Development and Reform Commission, said at a press conference last week.

The shift will likely also mean a decrease in funding for big-ticket infrastructure projects, which have already been on the decline in recent years, experts say.

“This also reflects the reality that the Chinese economy is slowing down – China doesn’t have as many resources to squander along BRI as it did during the first decade,” said Yun Sun, director of the China Program at the Stimson Center think tank in Washington.

Ten years on, Chinese decision makers are becoming “more selective and more calculating” about the benefits of their financing, she said. “Now they have new focuses.”