The Peregrine spacecraft — which launched last week on the first US mission to aim for a moon landing in over 50 years — is headed back toward Earth and expected to make a fiery reentry after a critical fuel leak dashed its lunar ambitions.

The failed moon landing attempt is a setback for NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services, or CLPS, program, which recruits private companies to help the space agency investigate the lunar surface as it aims to return humans to the moon later this decade.

Astrobotic Technology, the company that developed the Peregrine lander under a $108 million contract with NASA, revealed Sunday that it made the decision to dispose of the spacecraft by allowing it to disintegrate midair while plunging back toward Earth.

“While we believe it is possible for the spacecraft to operate for several more weeks and could potentially have raised the orbit to miss the Earth, we must take into consideration the anomalous state of the propulsion system and utilize the vehicle’s onboard capability to end the mission responsibly and safely,” according to an update posted to the Pittsburgh-based company’s website. “We do not believe Peregrine’s re-entry poses safety risks, and the spacecraft will burn up in Earth’s atmosphere.”

The Peregrine vehicle’s impending demise comes after the spacecraft faced challenges while en route to the moon, including an “anomaly” that resulted in its solar-powered battery pointing away from the sun and the fuel leak that left the spacecraft without enough propellant to complete its planned mission to gently touch down on the lunar surface.

It’s not yet clear what caused the leak.

Astrobotic and NASA are expected to give further updates on the mission during a news conference at 12 p.m. ET on Thursday.

“It is a great honor to witness firsthand the heroic efforts of our mission control team overcoming enormous challenges to recover and operate the spacecraft,” said Astrobotic CEO John Thornton in a Sunday statement. “I look forward to sharing these, and more remarkable stories, after the mission concludes on January 18. This mission has already taught us so much and has given me great confidence that our next mission to the Moon will achieve a soft landing.”

Weighing disposal options

Astrobotic did have other options for disposing of the Peregrine lander.

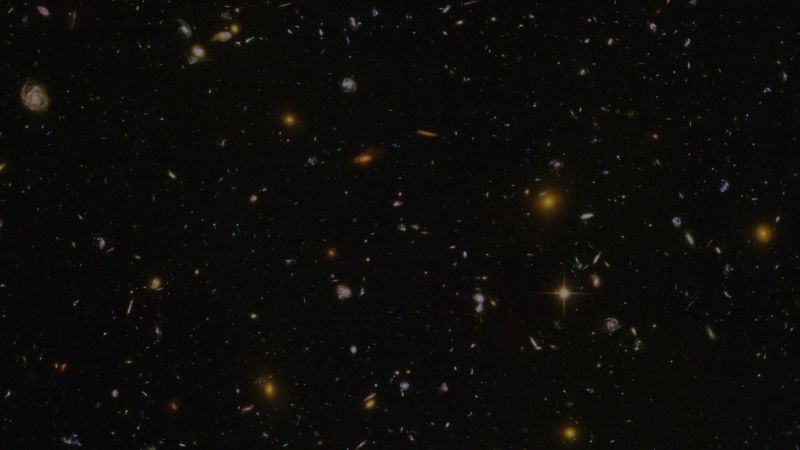

The spacecraft could have been left to the cosmos, destined to spend eternity in the dark expanse. But the company said it decided against that route considering the “risk that our damaged spacecraft could cause a problem.” The Peregrine lander would essentially become a piece of uncontrolled garbage, capable of smashing into other objects in space, such as operational satellites.

The company may have also considered allowing the Peregrine vehicle to crash-land on the moon, as many spacecraft have done — intentionally and unintentionally — on lunar missions of years past.

When it returns to Earth, the vehicle will be obliterated as it smashes into the planet’s thick atmosphere at high speeds. The company said its decision to bring Peregrine back came after receiving “inputs from the space community and the U.S. Government on the most safe and responsible course of action.”

Critical errors

If Peregrine had reached the moon, it might have become the first US spacecraft to land on the lunar surface since NASA’s Apollo 17 mission in 1972.

But the company acknowledged just hours after its spacecraft launched on January 8 that a soft landing on the moon would not be possible.

Astrobotic then switched course — aiming to operate the vehicle as a satellite as its tanks were drained.

Peregrine’s fuel leak slowed in the days following its launch, leaving the spacecraft with the ability to limp along for thousands of miles.

For the vast majority of the mission, the Peregrine lander has been controlled solely by its attitude control thrusters, which are tiny engines mounted to the side of the lander and designed to maintain stability or make precision movements.

At one point, the company said it was able to briefly power on one of the spacecraft’s main engines, which are designed to give up to three bursts of power to push the Peregrine lander farther out toward the moon after reaching space.

But — because of the fuel leak — long, controlled burns of the main engines were impossible, Astrobotic said.

As of Monday, the company said the spacecraft was about 218,000 miles (351,000 kilometers) from Earth.

What Peregrine could and couldn’t accomplish

Astrobotic was able to power on some of the science instruments and other payloads on board the lander.

Two of NASA’s five payloads — the Neutron Spectrometer System and the Linear Energy Transfer Spectrometer — were able to gather data on radiation levels in space, the space agency announced in a January 11 news release. While NASA had hoped to take those measurements on the lunar surface — where it’s planning to return astronauts later this decade — space agency officials indicated the data was still valuable.

The Peregrine lander was also able to activate a new sensor, developed by NASA, that was designed to help the spacecraft land on the moon. Called the Navigation Doppler Lidar, it uses lasers and the Doppler effect — which employs wave frequency to measure distance — to make precision navigations.

“Measurements and operations of the NASA-provided science instruments on board will provide valuable experience, technical knowledge, and scientific data to future CLPS lunar deliveries,” said Joel Kearns, the deputy associate administrator for exploration with NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, in a statement.

But at least one of NASA’s science instruments — the Laser Retroreflector Array — was not able to function. The LRA is a collection of eight prisms embedded in aluminum that can reflect lasers and relay precise locations. NASA engineers designed the array to become a permanent feature on the moon, helping other spacecraft orient their locations.

Likewise, an array of other payloads designed specifically to operate on the moon remain trapped aboard the Peregrine lander. They include a rover developed at Carnegie Mellon University and five tiny robots from the Mexican Space Agency that were designed to be catapulted onto the lunar surface.

The Peregrine spacecraft is also carrying various mementos, letters and even human remains that customers paid to fly on the mission.