When wildfire ripped through Hawaii’s Maui last August, the impact was devastating: a whole town reduced to ashes, more than 100 lives lost. The inferno was described as the “largest natural disaster in state history.”

But some on Instagram suggested, without evidence, there was something much more nefarious at play.

Wellness influencer @truth_crunchy_mama told her 37,000 followers to “stop blaming things on nature that were actually caused by the government.” They’re “going to keep setting wildfires until we all submit to their climate change agenda,” she said in another post.

Health influencer @drmercola suggested to his 504,000 followers whether, while the media focused on climate change, the fires might have been deliberately set to “to facilitate a land grab” to make the area a “smart city” — referring to a technology-focused urban design idea.

A natural parenting influencer, whose Instagram page is filled with soft-focus pictures of herself against pretty pastel backgrounds, inferred to her 76,000-strong community that Hawaii’s wildfires were started by “directed energy weapons” — systems which use energy such as laser beams.

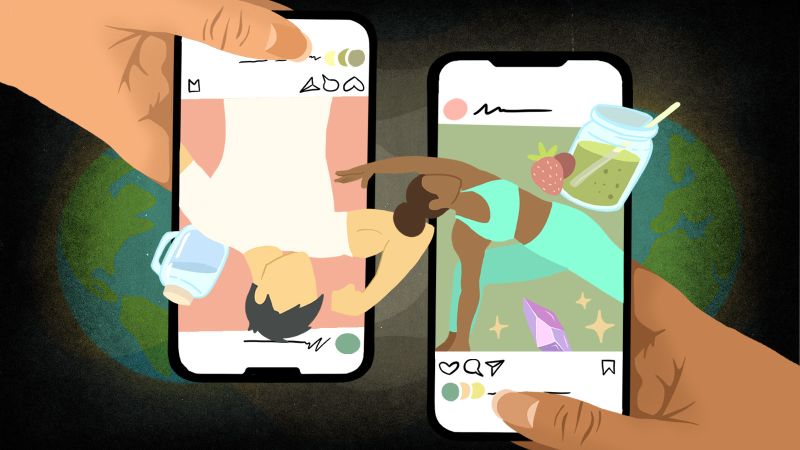

These posters are all wellness influencers — a loosely-defined umbrella term for a wide range of accounts including yoga, lifestyle, fitness, alternative health and new age spirituality.

While conspiracy theories about the Hawaii wildfires spread across the internet last year, it may seem surprising they were also seized upon by part of the wellness community.

But for years there has been a merging of wellness, disinformation and conspiracy, as a subset of influencers use the backdrop of aesthetically pleasing, pastel-colored posts to spread much darker messages, weaving together alarming conspiracy theories with calls for users to buy their supplements or services.

This phenomenon exploded during the pandemic, when anti-vax sentiment took hold in large parts of the wellness community. As interest in the pandemic waned, experts say some wellness influencers have latched on to climate change to galvanize followers.

Their concern: Those influencers — some with hundreds of thousands of followers — are exposing new, and younger, audiences to a slew of misinformation and undermining efforts to tackle the climate crisis.

Simmons, also a researcher at the Institute for Strategic Dialogue, a UK-based think tank focused on disinformation, started digging. She pored over more than 150 wellness accounts, most of which had between 10,000 to 100,000 followers. All offered wellness advice, sold related products and promoted some form of misinformation.

The claims Simmons found were sweeping and varied, ranging from outright climate denial to attempts to undermine climate solutions by portraying them as part of a global plot for control.

Some focused on deadly extreme weather events, saying they were orchestrated by the government, or that malign global forces were modifying the weather. Others claimed climate policies were a plot to control people’s lives, bodies and diets. A small section of new age accounts asserted that climate change was the result of a disconnection with forces in the universe.

Rejecting climate action may seem counterintuitive for wellness influencers, who often focus on nature or evoke bucolic visions of the past. But when you have insight into this world, it tracks, Simmons said.

A strong thread of individualism runs through wellness accounts, alongside a deep distrust of authorities. “They emphasize individual solutions to collective problems, and they sell wellness as a response to climate anxiety,” she said.

Some even say they accept the human-caused climate crisis.

His climate posts are often framed in this way, not making definitive claims but rather asking questions like: Is the idea of eating insects “part of globalists’ ‘green agenda?’” Or advertising guest posts suggesting the “war on climate change” follows “the same playbook used by nefarious individuals who lust for complete power over the citizens.”

‘Dangerous rhetoric’

The wellness industry, depending on how its defined, is worth anything from many billions to trillions of dollars — $5.6 trillion, according to a recent report from industry group The Global Wellness Institute.

And it’s been decades in the making. Its modern incarnation goes back to the late 1950s, said Stephanie Alice Baker, who researches health and wellness cultures at City University in the UK. American doctor Halbert L. Dunn started to popularize the idea that health was more than simply the absence of disease; instead “peak wellness” meant also finding purpose and meaning.

The movement gained traction around the 1970s, then with the internet, came the entrepreneurs and influencers. Wellness has now come to mean almost anything, said Baker, but at its core it revolves around ideas of individualism, self-enlightenment and distrust of institutions — a near-perfect breeding ground for conspiracy theories to flourish.

“I don’t think the culture understood how dangerous the rhetoric in wellness spaces was until the pandemic,” said Derek Beres, co-host of the podcast Conspirituality, which explores the collision between wellness and conspiracy theories. One researcher, Marc-André Argentino, coined the term “pastel QAnon,” to describe the soft, pleasing aesthetic used by some influencers to spread their conspiratorial worldview.

Influencers crave relevance, said Callum Hood, head of research at the Center for Countering Digital Hate, and “climate change is a big relevant issue that’s in the news all the time.”

Misinformation expert Tim Caulfield, a professor of health law and policy at the University of Alberta, said many wellness influencers are now expected to present a basket of beliefs that the community wants to hear. “Being anti-climate change becomes part of being on that team” and a way to “turbocharge your audience,” he added.

It may seem easy to dismiss this subsection of wellness influencers, but the bonds they create with followers are strong.

They are particularly good at creating intimacy, because they focus on people’s bodies and direct experience of the world, said Baker. It forges a strong parasocial — or one-sided — connection, where followers believe they have a personal relationship with the influencer. Many project authenticity and present themselves as outside the system, able to speak truth to power, she added.

The appeal of their conspiracy messages is clear, especially with a complex issue like climate change. It is a salve to anxiety and a chance to reclaim agency. “Once you find the conspiracy theory, it all collapses, it all becomes simplified. ‘There’s a bad guy who’s lying to you,’” CCDH’s Hood said.

The anger fuels engagement, but how this translates to real-world impact is notoriously hard to pin down.

Still, many experts think there is a significant effect. Climate misinformation is having “a profound impact” both on people’s beliefs and on the normalization of fringe perspectives, Caulfield said. Not only does it undermine climate solutions, it also depoliticizes people, sowing distrust in climate policies.

It’s particularly worrying as it allows climate misinformation to reach new audiences, experts say, including young people that might otherwise be supportive of climate change action.

Studies suggest younger generations are getting the majority of their news from platforms like Instagram, said Mariah Wellman, an assistant professor and wellness expert at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Countering misinformation

Extreme views can give influencers higher clicks, more audience and a more lucrative brand, Caulfield said, so the incentive is clear to steer towards those ideologies. “And the sad thing is that, the more it becomes about ideology, the harder it is to change people’s minds, because it is about belonging to a community.”

There are strategies to counter the misinformation, though. It’s important to do it in a respectful and constructive way, even when it comes from influencers some may dismiss as “frivolous,” Caulfield said. “Pre-bunking” can also help, he added — getting out ahead of the misinformation, and making people aware of the tactics used to push it.

For others, the focus is much more on the other platforms hosting these influencers. Hood is pushing for more clarity on climate policies, and for measures including bans on amplifying and monetizing content that clearly contradicts climate science.

He also called on regulators to take a hard look at the products and services being sold on Instagram and other platforms. “It is the Wild West,” he said.

Meta, which owns Instagram, declined to comment. The company has policies to counter misinformation, including international teams of fact checkers which evaluate climate science content. When they rate posts as false, they can reduce distribution and add warning labels, and accounts that repeatedly offend can lose the ability to advertise or monetize.

But for experts like Hood, there is simply not enough being done to tackle a problem with such alarming implications.

As the climate crisis continues to fuel more frequent and more severe extreme weather events, it is creating perfect conditions for climate denial and misinformation to flourish across these parts of the wellness community.

“The dark side of wellness has always been there. It’s just now we see it,” Simmons said.